This is the sixth new place in just over two years.

I don't think of myself as a wandering kind of guy. There are tons of foreigners here who blow most of their language teaching salaries on jaunts around Asia, treks to Thailand, Indonesia, China or India squeezed in on a week's vacation. Skews your sense of reality when it's no big deal to hear that someone got a few days off and few to Hong Kong "just to see what it's like." I have pretty much stayed put, both out of a desire to save money and because I always felt there was enough fascinating stuff just around my neighborhood.

Which leads to a lot of cold Japanese Christmases, but has also produced some of my best Japan stories ever. Last winter break my brother came to visit me in Japan, and during New Years we crammed in with several thousand of our closest friends to get luck for the New Year at one of Kyoto's shrines, then ended up in a whole in the wall bar packed ear to ear at long bamboo tables drinking beer. I would be hard pressed to explain how it was we ended up in a massive graveyard overlooking the city with six brand new friends; one loud mouthed Osaka girl who had been ecstatic to show us her grandfather's grave a few minutes before broke down in front of it, The guys behind us stopped the ghost jokes when she began to give a sloppy drunken homage to her grandfather, begging him to forgive her for not coming by more often.

But back to apartments. Somehow I've ended up moving like crazy during my time here, starting at an English teacher job in the deep mountains of Shizuoka's tea country, where my neighbor was a guy of uncertain nationality who called himself Mike and had natural sounding if limited English. I would see him out occasionally with a team of Brazilian day laborers who wore full white jumpsuits, the handful of them waitng by the side of the road with canned vending machine coffee, waiting for their ride, or scooting away somewhere in a van. I don't think it was any coincidence that all the foreigners in town stayed in one apartment block. I housesat in a tidy three room apartment with a garden for six months a colleague while she was away. Then subletted a room in a wonderful old, well kept two story house with a pathological perfectionist for a housemate.

"Jamie, why did you not lock the door? There are many people who could steal our things."

"I walked across the street to get better cell phone reception. It never left my sight!"

"Yes, but you know that these people are very clever."

". . ."

A farmhouse in Yamagata, a wind rattled duplex in a suburb city of Tokyo. Both living in close quarters with people I was working everyday. Which has it's ups and downs. Downs being you don't bring girls over and serve them dinner and drink wine.

Apartment #6 is shaping up to about the same pros and cons as the rest. The rent is reasonable, I didn't get screwed into paying any reikin (literally "respect money") to the landlord, it's a three minute hop from the station, and is smack in the middle of downtown. More precisely it is on the fourth floor of a building that houses an Indian restaurant (first floor), a mysterious business called "Club Maria", which I read off it's faded black doormat, and a beauty salon called "La Reve", and a Karaoke Bar called "OZ2". The karaoke bars noise doesn't waft up to the fourth floor, but everytime I step out my front door I step into the unmistakable odor of real Indian curry.

As I was moving my last few things in the other day I finally met my next door neighbor, an Indian man whose age I can't quite place. We said our hellos and chatted a bit in his stuttered but usable English, and he told me he'd been here for nine years, and that he owns the restaurant on the first floor. Suddenly it all clicked into place: the authentic Indian restaurant, the only place I looked at that said ok to a foreigner. I promised I'd stop by his restaurant for lunch sometime, and we shook hands, off to work. He went to stew out curries for Japanese looking for a taste of the exotic, and I went to teach English to middle aged women seeking the same.

Tuesday, February 22, 2005

Thursday, February 17, 2005

regret

Ughh... whoa. What was that all about. I sit down last night after dinner to write a little something about my ambiguous relationship with television, and it turns into this massive sprawling multi-linked monster of a post. I was 100% sober, but it's like I was possessed. I wake up this morning and the thought popped open as soon as my eyes did: "What the hell? Television?!" That does it. No TV in the new place fer sure. I'm resolved. From now on this blog will just be a running commentary of my reading of Moby Dick.

My friend Seth has "invented" a new word (or at least created a word unaware that it already existed). While mostly meant to refer to a massive blog makeover, I prefer his meaning of the feelings of regret the day after a blog post for the word blogover.

My friend Seth has "invented" a new word (or at least created a word unaware that it already existed). While mostly meant to refer to a massive blog makeover, I prefer his meaning of the feelings of regret the day after a blog post for the word blogover.

Wednesday, February 16, 2005

boob tube

Tomorrow I head down to the real estate agency to have a cup of tea with my new landlord, have a little chit-chat, and get the key to my new place. I'll start moving in tomorrow, the utilities will be on by February 20th, and I'll be sleeping there from March 1st. Since one of my housemates is moving into his girlfriend's fully furnished apartment, he's been nice enough to give me several of his appliances here. All of this leaves me with a philosophical crisis. TV or no TV?

Somewhere in the middle of high school I lost interest in television. I remember one particular day being absolutely exhausted, getting home late from school jazz band practice while the family was clustered around watching Seinfeld. "Jamie, you have to see this! George and Kramer are..." and in that moment I was swamped with this overwhelming angsty teenage feeling of alienation from my family. I mean, for real, not like what everyone feels in high school, this was, like, totally unique. Really.

Fast forward to a few years later as an exchange student in Japan, living with a few foreign and Japanese housemates in a drafty two story fire trap in the Kyoto suburbs. Sunday nights were reserved for huddling around the idiot box and watching Warau Inu no Boken (Adventures of a Laughing Dog), this sketch comedy show put on by five of Japan's best comedians. Like Monty Python, a lot of Japanese humor relies on non sequitur and bizarre juxtapositions that don't make much sense, so even with my bare bones Japanese I didn't need much translation. Sexy cow femme fatales, three guys in crow costumes doing coordinated dance moves and ending every phrase with a long drawn out "kaaaaaaaaaaa" and a magical male cheerleader squad who prance around in nothing but oversized leaves over their privates: this is the Esperanto of comedy.

When I came back to Japan in the summer of 2002, Warau Inu had just been cancelled, and I didn't have any nerdy housemates to translate for me, so the TV that had come with my apartment got shoved in the closet and made occasional appearances as a movie-tron.

But lately I've suddenly found myself sucked into the hyper-frenetic world of Japanese TV again. Everything is fascinating, brain melting eye candy. There are the stunningly produced reality surpassing 15 second ads that seem to be inserted into shows at random. There is the Friday night comedy variety show Warakin where the best new comedians cut their chops against each other. There is the unbelievable Dochi no Ryori, where two master chefs prepare two opposing styles of meals using some of the finest ingredients in the world, and seven celebrity guests have to choose which one they will eat. Whoever chooses in the majority gets to eat the meal, whoever chooses in the minority has to sit and watch them enjoy the meal without eating anything.

Then there is the nightly parade of unbelievably weird stuff. The TV Asahi evening news is without a doubt Japan's worst news program; their anchor is a former sports announcer, they usually lead off with some fluffy scandal or murder story, and wrap up with stuff like robots that can do traditional Japanese dance.

Stupid? Yes. Mindless? Sorta. Consumer brainwashing? No doubt. Useless? Well, it helps my Japanese and gives me conversation fodder. So what's the use of Japanese TV? Well, in my mind, American TV takes itself way seriously. Even from here I see discussions of the Super Bowl ads in major newspapers, the cancellation of Friends makes the cover of Newsweek and a bevy of critics who retroactively praise its historical importance. Yes, Friends. Japanese TV has no such pretensions. It is designed to be perfectly inane, sidebars and subtitles letting the viewer understand who's talking about what in about three seconds. It doesn't try to be anything more than a mindlessly entertaining diversion that you flip on for a few minutes during dinner.

But then again my room is cluttered with a bass slowly going out of tune, a half finished copy of Moby Dick, a few barely used cookbooks, and a poor lonely journal that has fallen into disuse since this blog started. I could be out organizing against the bullshit. But if I ditch the TV, I will sorely miss my new favorite Japanese comedian Hiroshi. His entire shtick is to stand slightly askew in a spotlight on a darkened stage, a slow jazz ballad sung in Portuguese playing behind him. He will spin out slightly bizarre one liners about his sad sack life in a slow monotone that hovers between feeble resolve and self pity.

"I am Hiroshi. Why is it that even though I haven't touched any, my hands always smell like freshly cut grass?" "I am Hiroshi. The seat of my bicycle is gone!" "I am Hiroshi. If I had a chihuahua, would you come hang out at my apartment?" "I am Hiroshi. If I could play a flute made out of fish paste, do you think I could get on TV?"

This is gonna be a tough decision.

Somewhere in the middle of high school I lost interest in television. I remember one particular day being absolutely exhausted, getting home late from school jazz band practice while the family was clustered around watching Seinfeld. "Jamie, you have to see this! George and Kramer are..." and in that moment I was swamped with this overwhelming angsty teenage feeling of alienation from my family. I mean, for real, not like what everyone feels in high school, this was, like, totally unique. Really.

Fast forward to a few years later as an exchange student in Japan, living with a few foreign and Japanese housemates in a drafty two story fire trap in the Kyoto suburbs. Sunday nights were reserved for huddling around the idiot box and watching Warau Inu no Boken (Adventures of a Laughing Dog), this sketch comedy show put on by five of Japan's best comedians. Like Monty Python, a lot of Japanese humor relies on non sequitur and bizarre juxtapositions that don't make much sense, so even with my bare bones Japanese I didn't need much translation. Sexy cow femme fatales, three guys in crow costumes doing coordinated dance moves and ending every phrase with a long drawn out "kaaaaaaaaaaa" and a magical male cheerleader squad who prance around in nothing but oversized leaves over their privates: this is the Esperanto of comedy.

When I came back to Japan in the summer of 2002, Warau Inu had just been cancelled, and I didn't have any nerdy housemates to translate for me, so the TV that had come with my apartment got shoved in the closet and made occasional appearances as a movie-tron.

But lately I've suddenly found myself sucked into the hyper-frenetic world of Japanese TV again. Everything is fascinating, brain melting eye candy. There are the stunningly produced reality surpassing 15 second ads that seem to be inserted into shows at random. There is the Friday night comedy variety show Warakin where the best new comedians cut their chops against each other. There is the unbelievable Dochi no Ryori, where two master chefs prepare two opposing styles of meals using some of the finest ingredients in the world, and seven celebrity guests have to choose which one they will eat. Whoever chooses in the majority gets to eat the meal, whoever chooses in the minority has to sit and watch them enjoy the meal without eating anything.

Then there is the nightly parade of unbelievably weird stuff. The TV Asahi evening news is without a doubt Japan's worst news program; their anchor is a former sports announcer, they usually lead off with some fluffy scandal or murder story, and wrap up with stuff like robots that can do traditional Japanese dance.

Stupid? Yes. Mindless? Sorta. Consumer brainwashing? No doubt. Useless? Well, it helps my Japanese and gives me conversation fodder. So what's the use of Japanese TV? Well, in my mind, American TV takes itself way seriously. Even from here I see discussions of the Super Bowl ads in major newspapers, the cancellation of Friends makes the cover of Newsweek and a bevy of critics who retroactively praise its historical importance. Yes, Friends. Japanese TV has no such pretensions. It is designed to be perfectly inane, sidebars and subtitles letting the viewer understand who's talking about what in about three seconds. It doesn't try to be anything more than a mindlessly entertaining diversion that you flip on for a few minutes during dinner.

But then again my room is cluttered with a bass slowly going out of tune, a half finished copy of Moby Dick, a few barely used cookbooks, and a poor lonely journal that has fallen into disuse since this blog started. I could be out organizing against the bullshit. But if I ditch the TV, I will sorely miss my new favorite Japanese comedian Hiroshi. His entire shtick is to stand slightly askew in a spotlight on a darkened stage, a slow jazz ballad sung in Portuguese playing behind him. He will spin out slightly bizarre one liners about his sad sack life in a slow monotone that hovers between feeble resolve and self pity.

"I am Hiroshi. Why is it that even though I haven't touched any, my hands always smell like freshly cut grass?" "I am Hiroshi. The seat of my bicycle is gone!" "I am Hiroshi. If I had a chihuahua, would you come hang out at my apartment?" "I am Hiroshi. If I could play a flute made out of fish paste, do you think I could get on TV?"

This is gonna be a tough decision.

Sunday, February 13, 2005

distillation

I'm gonna miss my housemates.

It's official, I'm moving out of my place by the end of the month, to a single apartment on the other, cooler side of the station where hole-in-the-wall noodle shops vie for space with national chain izakaya bars and the exciting world of shopping takes place. My current neighborhood mostly involves men making houses for people to sleep in and people who stumble back from Tokyo at 11 at night to enjoy the wonderful world of sleeping. I haven't smelled much fish or curry wafting out of kitchen fans in my neighborhood so I figure most people go out to eat. The doorway of my old-old place in rural Saitama was placed right next to the kitchen exhaust of the place next door, giving me an olfactory preview of their nightly meal. They really liked grilled mackerel.

I'm not gonna drag my housemates into this blog any farther than to say that one of them has introduced me to the wonderful world of Japan's hot new liquor shochu. All of you stateside will have to tell me if this has seeped over to the US at all. (I doubt it.) Distilled from barley, rice, sweet potatoes or just about anything, shochu is going through a bit of a boom in Japan right , leaving fermented sake in the dust as a drink for smelly old men and weird foreigners who wanna experience "Japanese culture." Shochu bars which specialize in the finer brands from Kyushu and Chugoku in the muggy climes of South-Western Japan are popping up in Tokyo's chicest neighborhoods and as the watering holes of characters in TV dramas.

I'll admit, it took me a while to get used to the stuff. It's the first hard liquor I've ever developed a taste for; up till now beer and wine were the only types of alcohol that enlightened my mouth as well as my brain. The first time I had it was at an enkai (drinking party) during my first year here as an English teacher. The town's superintendant of schools, a remarkably dapper man who was pushing 60, unmarried, and read obsessively until the wee hours, subsisting on 3 to 4 hours of sleep a night, offered me a cup towards the end of one night of epic silliness. Japanese drinking parties seem designed to make you sick: you have to drink a few glasses of beer first, then everyone branches off into their own personal faves, with people sampling just about everything on the menu while Mitsuda from accounting does magic tricks. The superintedant is just pressing for you to try his favorite shochu, right after you've tried Matsuda's whiskey, Hashimoto's warm sake and Yamada's homemade plum liquor. I learned to just politely refuse and stick to the bottles of Japanese domestic beer.

The other times I had shochu it was cut with something else, like coke or tea. It also forms the alcoholic base for chu-hi, these canned shochu-hiballs flavored with lemon, plum or something else fruity and sweet. Hey man, when I wanna drink soda, I'll drink soda, what's up with a liquor that can't hold it's own?

But in these windy winter nights my housemate has convinced me of the joys of 4 parts cheap-but-decent shochu, cut with 6 parts hot water, fragrance rising up out of your mug; one cup a nightcap, two a shitty day at work and three a real party. As I sit here flying on number three (or four?), housemate at the computer next to me surfing god-knows-what on the internet, the mellow drink leaving me both relaxed and giddy, I'm comforted by one of shochu's legendary properties:

no hangover.

The closest thing I've got to a digital camera is this little thing on my cell phone which renders all photos in a pixellated digital haze.

It's official, I'm moving out of my place by the end of the month, to a single apartment on the other, cooler side of the station where hole-in-the-wall noodle shops vie for space with national chain izakaya bars and the exciting world of shopping takes place. My current neighborhood mostly involves men making houses for people to sleep in and people who stumble back from Tokyo at 11 at night to enjoy the wonderful world of sleeping. I haven't smelled much fish or curry wafting out of kitchen fans in my neighborhood so I figure most people go out to eat. The doorway of my old-old place in rural Saitama was placed right next to the kitchen exhaust of the place next door, giving me an olfactory preview of their nightly meal. They really liked grilled mackerel.

I'm not gonna drag my housemates into this blog any farther than to say that one of them has introduced me to the wonderful world of Japan's hot new liquor shochu. All of you stateside will have to tell me if this has seeped over to the US at all. (I doubt it.) Distilled from barley, rice, sweet potatoes or just about anything, shochu is going through a bit of a boom in Japan right , leaving fermented sake in the dust as a drink for smelly old men and weird foreigners who wanna experience "Japanese culture." Shochu bars which specialize in the finer brands from Kyushu and Chugoku in the muggy climes of South-Western Japan are popping up in Tokyo's chicest neighborhoods and as the watering holes of characters in TV dramas.

I'll admit, it took me a while to get used to the stuff. It's the first hard liquor I've ever developed a taste for; up till now beer and wine were the only types of alcohol that enlightened my mouth as well as my brain. The first time I had it was at an enkai (drinking party) during my first year here as an English teacher. The town's superintendant of schools, a remarkably dapper man who was pushing 60, unmarried, and read obsessively until the wee hours, subsisting on 3 to 4 hours of sleep a night, offered me a cup towards the end of one night of epic silliness. Japanese drinking parties seem designed to make you sick: you have to drink a few glasses of beer first, then everyone branches off into their own personal faves, with people sampling just about everything on the menu while Mitsuda from accounting does magic tricks. The superintedant is just pressing for you to try his favorite shochu, right after you've tried Matsuda's whiskey, Hashimoto's warm sake and Yamada's homemade plum liquor. I learned to just politely refuse and stick to the bottles of Japanese domestic beer.

The other times I had shochu it was cut with something else, like coke or tea. It also forms the alcoholic base for chu-hi, these canned shochu-hiballs flavored with lemon, plum or something else fruity and sweet. Hey man, when I wanna drink soda, I'll drink soda, what's up with a liquor that can't hold it's own?

But in these windy winter nights my housemate has convinced me of the joys of 4 parts cheap-but-decent shochu, cut with 6 parts hot water, fragrance rising up out of your mug; one cup a nightcap, two a shitty day at work and three a real party. As I sit here flying on number three (or four?), housemate at the computer next to me surfing god-knows-what on the internet, the mellow drink leaving me both relaxed and giddy, I'm comforted by one of shochu's legendary properties:

no hangover.

The closest thing I've got to a digital camera is this little thing on my cell phone which renders all photos in a pixellated digital haze.

Thursday, February 10, 2005

21st century dating

When I was in college and gleefully chewing up Japanese literature, one of my favorite novels was Kagi (The Key) by Junichiro Tanizaki. Written in 1956, the story is a remarkable experimental work, taking the form of two diaries of a married couple detailing their sexual life and innermost thoughts. The chapters alternate between the diaries, and while they start out independent of each other, the couple and the reader gradually begin to realize they've been reading each other's secret diaries, and that what's being written is not so much the truth as another level of the power play in their relationship. It is a psychologically stunning book, twisting your head around every word to see if it is "true" or just written for the other person's benefit.

The other night after penning that last blog entry I ended up kicking around the internet, found some blogs where people wrote about their dating life. I poked around half interested, but my eyes shot wide open, I stood straight up and just went dumb when I found that in two completely independent websites two people were blogging about dating each other, writing as if the other person wasn't reading. The girl is part of some public blog thing where you write about your dating life, the guy just includes that stuff regularly in his blog. They both mention the fact that the other person is blogging the relationship, but they don't let on any reservations about this whatsoever. They even wrote when and where they slept with each other. But they still insist on blogging about each other under aliases. I mean, there's something to be said for people who anonymously blog their dating life, but they and their partners are usually anonymous, right? These two have their photos and contact info right next to the blow-by-blow of their dates!

My mind has really been reeling from this. Both these people seem relatively normal. Well, as normal as wealthy New York yuppies can be. The biggest complaint the guy has written in his blog (February 9th entry) is that the windows in his high rise apartment are way to big, and he's worried that the lawyers across the street think he's some kind of playboy because of all the beautiful women that are constantly coming and going. I hate it when that happens.

This totally raises all kinds of "The Key" type issues. For instance, when they go on a date are they both thinking about how to write about it, and worrying about what the other person is gonna write? Do they check the other's blog the next day? (Of course they do.) So then they're writing as much for the other person as for the general audience. I'm having a hard time actually believing these people are real, that they could actually be going through with this.

If Tanizaki hadn't written that book fifty years ago I would have said this is truly something completely new under the sun, but I suppose it's just the latest version of the eternal fascination with the love lives of the young and wealthy. But now we get to watch the machinations unfold day-by-day. I'd rather read a novel. With real people it's just... icky.

The other night after penning that last blog entry I ended up kicking around the internet, found some blogs where people wrote about their dating life. I poked around half interested, but my eyes shot wide open, I stood straight up and just went dumb when I found that in two completely independent websites two people were blogging about dating each other, writing as if the other person wasn't reading. The girl is part of some public blog thing where you write about your dating life, the guy just includes that stuff regularly in his blog. They both mention the fact that the other person is blogging the relationship, but they don't let on any reservations about this whatsoever. They even wrote when and where they slept with each other. But they still insist on blogging about each other under aliases. I mean, there's something to be said for people who anonymously blog their dating life, but they and their partners are usually anonymous, right? These two have their photos and contact info right next to the blow-by-blow of their dates!

My mind has really been reeling from this. Both these people seem relatively normal. Well, as normal as wealthy New York yuppies can be. The biggest complaint the guy has written in his blog (February 9th entry) is that the windows in his high rise apartment are way to big, and he's worried that the lawyers across the street think he's some kind of playboy because of all the beautiful women that are constantly coming and going. I hate it when that happens.

This totally raises all kinds of "The Key" type issues. For instance, when they go on a date are they both thinking about how to write about it, and worrying about what the other person is gonna write? Do they check the other's blog the next day? (Of course they do.) So then they're writing as much for the other person as for the general audience. I'm having a hard time actually believing these people are real, that they could actually be going through with this.

If Tanizaki hadn't written that book fifty years ago I would have said this is truly something completely new under the sun, but I suppose it's just the latest version of the eternal fascination with the love lives of the young and wealthy. But now we get to watch the machinations unfold day-by-day. I'd rather read a novel. With real people it's just... icky.

nippon vs. north korea

I set out two unspoken goals in this blog: 1) no writing about "that wacky stuff in Japan" and 2) no whining about my personal life. Well, I broke up #1 with my last post, so I might as well muck up #2 as best I can.

Tonight was the Japan vs. North Korea World Cup qualifier game, and I was invited out to a night of beer and soccer by an English teacher friend. While North Korea sometimes crops up onto the Op-Ed pages in the US, it is a daily issue in Japan. In addition to all their nukes, the North Korean government has taken dozens of Japanese hostages from the rural Sea of Japan coast, and the relatives of these hostages are a major political and morally righteous force in Japan, appearing almost daily on the local news, pressuring the government to further action against North Korea. There was a man outside my local station today with handdrawn cardboard signs and a petition that called for harder sanctions against North Korea in light of the hostage situation.

On the other hand, North and South Korea were colonized by Japan from 1910-1945: Japanese was made the official language and thousands of Koreans were forced into heavy labor projects, many in Japan. The Japanese postwar "economic miracle" was given a big boost when Japan was the main base and supplier of the US army during the Korean war. To this day many North Koreans who were forced into labor in Japan during the war are stranded here, denied Japanese citizenship, passports, or decent employment prospects.

It was in this context that Japan happened to be randomly selected to face off against North Korea in the first game of the World Cup qualifiers. The game was to be held in Japan, which subsequently chose my good old soccer crazy city of Urawa as the site of the match. Tickets sold out in 10 minutes.

In all fairness, the Japanese media was careful to distinguish between the North Korean government and the soccer team. The team was met with flowers and hordes of North Koreans fans who choose Japan and disenfranchisement over North Korea and dictatorship. But aside from all the expressions of good will, this was more than just another soccer game, these were gladiators in an arena.

There were nine or ten of us out tonight to see the game, about half English teachers living the fantasy life, half Japanese struggling in whatever work they can find and little ole me. The first bar we tried was packed full of fans, but the second had a line of tables just our size. The name of the place hung above the bar in neon, Modern Times: Restaurant and Bar. The staff reflected the modernity of the bar: the bartender had elaborately styled hair, wore a brand name button down shirt, and the only waiter in the place was dressed in a remarkably elaborate cowboy outfit.

I sat next to a Japanese guy about my age who was crazy about reggae and Japanese soccer. Across from me was a massage therapist/unwanted hair remover who was a soccer maniac and a cute and nervous librarian who was not. Japan scored one goal in the first few minutes. The reggae guy and I talked about MC's and clubs. North Korea scored a goal. The librarian and I talked about Japanese mystery writers. In the second half I actually watched the game. Japan scored in the last few minutes and the bar exploded into a round of toasting and drinking.

The soccer march ended with Japan winning 2-1. People trickled off until just five of us were left. The librarian had left me with a list of good authors and no phone number. The bill came out to more than we expected, and the five of us barely coughed it up. I suddenly realized there were two brand new couples and myself. We stumbled home in the bitter February air, brushing past the mahjong dens and massage parlors.

I waved goodbye to the massage therapist and her new boyfriend as I stepped onto the last train home. Sitting across from me was a man in his late 30's with the exact same type of Korean made backpack I used to own, tinted prescription glasses, an entirely waterproof outfit and a real utility belt with two pockets bulging off of his left hip. At one point he saved his seat with the backpack and ran to tell the conductor that someone had boarded without a ticket, who was subsequently booted out, no more trains left to catch. The guy picked his nose for the five minutes before my stop. After I got off I glanced back to see him and my old backpack slide away into the night, me alone on the platform and him strangely content, his index finger probing up his left nostril.

Tonight was the Japan vs. North Korea World Cup qualifier game, and I was invited out to a night of beer and soccer by an English teacher friend. While North Korea sometimes crops up onto the Op-Ed pages in the US, it is a daily issue in Japan. In addition to all their nukes, the North Korean government has taken dozens of Japanese hostages from the rural Sea of Japan coast, and the relatives of these hostages are a major political and morally righteous force in Japan, appearing almost daily on the local news, pressuring the government to further action against North Korea. There was a man outside my local station today with handdrawn cardboard signs and a petition that called for harder sanctions against North Korea in light of the hostage situation.

On the other hand, North and South Korea were colonized by Japan from 1910-1945: Japanese was made the official language and thousands of Koreans were forced into heavy labor projects, many in Japan. The Japanese postwar "economic miracle" was given a big boost when Japan was the main base and supplier of the US army during the Korean war. To this day many North Koreans who were forced into labor in Japan during the war are stranded here, denied Japanese citizenship, passports, or decent employment prospects.

It was in this context that Japan happened to be randomly selected to face off against North Korea in the first game of the World Cup qualifiers. The game was to be held in Japan, which subsequently chose my good old soccer crazy city of Urawa as the site of the match. Tickets sold out in 10 minutes.

In all fairness, the Japanese media was careful to distinguish between the North Korean government and the soccer team. The team was met with flowers and hordes of North Koreans fans who choose Japan and disenfranchisement over North Korea and dictatorship. But aside from all the expressions of good will, this was more than just another soccer game, these were gladiators in an arena.

There were nine or ten of us out tonight to see the game, about half English teachers living the fantasy life, half Japanese struggling in whatever work they can find and little ole me. The first bar we tried was packed full of fans, but the second had a line of tables just our size. The name of the place hung above the bar in neon, Modern Times: Restaurant and Bar. The staff reflected the modernity of the bar: the bartender had elaborately styled hair, wore a brand name button down shirt, and the only waiter in the place was dressed in a remarkably elaborate cowboy outfit.

I sat next to a Japanese guy about my age who was crazy about reggae and Japanese soccer. Across from me was a massage therapist/unwanted hair remover who was a soccer maniac and a cute and nervous librarian who was not. Japan scored one goal in the first few minutes. The reggae guy and I talked about MC's and clubs. North Korea scored a goal. The librarian and I talked about Japanese mystery writers. In the second half I actually watched the game. Japan scored in the last few minutes and the bar exploded into a round of toasting and drinking.

The soccer march ended with Japan winning 2-1. People trickled off until just five of us were left. The librarian had left me with a list of good authors and no phone number. The bill came out to more than we expected, and the five of us barely coughed it up. I suddenly realized there were two brand new couples and myself. We stumbled home in the bitter February air, brushing past the mahjong dens and massage parlors.

I waved goodbye to the massage therapist and her new boyfriend as I stepped onto the last train home. Sitting across from me was a man in his late 30's with the exact same type of Korean made backpack I used to own, tinted prescription glasses, an entirely waterproof outfit and a real utility belt with two pockets bulging off of his left hip. At one point he saved his seat with the backpack and ran to tell the conductor that someone had boarded without a ticket, who was subsequently booted out, no more trains left to catch. The guy picked his nose for the five minutes before my stop. After I got off I glanced back to see him and my old backpack slide away into the night, me alone on the platform and him strangely content, his index finger probing up his left nostril.

Monday, February 07, 2005

the nightcap of champions

I remember one summer before I'd ever come to Japan, before I even turned twenty-one, buying those oversized cans of Japanese beer you sometimes see in the important section of US liquor stores. My housemate and I just couldn't fathom what the hell was up with a can of beer that approached 2 liters. We poured the thing out into two glasses between the two of us and pondered the mystery. Now as an ex-pat with a few years under my belt I can confidently answer that the reason it's so big is because it's intended to be poured out among friends at a party.

I have always viewed the whole "look at all the wacky weird shit" in Japan mentality a little bit askew, because some people form these whole bullshit cultural theories off of the weird commercials on TV. Base, not superstructure people! Please. Where are your liberal arts educations anyway?

That being said, here's a picture of the 135 ml beer I'm drinking as I write this. Isn't it weird?

Why a beer so ridiculously small? I dunno, I figure the best part of beer is the first gulp. For the record, Kirin Ichiban Shibori is the best mass produced Japanese domestic, and just these few gulps have renewed my faith. =Those Japanese sure do like to make things small and convenient!=

That's the superstructure answer. The base answer is that my housemates went to a newly opened izakaya (Japanese style bar) in town, and they all got these micro-can beers as promotional take-home gifts. Funny, idn't it.

I have always viewed the whole "look at all the wacky weird shit" in Japan mentality a little bit askew, because some people form these whole bullshit cultural theories off of the weird commercials on TV. Base, not superstructure people! Please. Where are your liberal arts educations anyway?

That being said, here's a picture of the 135 ml beer I'm drinking as I write this. Isn't it weird?

Why a beer so ridiculously small? I dunno, I figure the best part of beer is the first gulp. For the record, Kirin Ichiban Shibori is the best mass produced Japanese domestic, and just these few gulps have renewed my faith. =Those Japanese sure do like to make things small and convenient!=

That's the superstructure answer. The base answer is that my housemates went to a newly opened izakaya (Japanese style bar) in town, and they all got these micro-can beers as promotional take-home gifts. Funny, idn't it.

Sunday, February 06, 2005

rinji jinsei

Last night was the monthly Kuchi Kuchi DJ event in Omiya, a mix of domestic and imported DJ's spinning an array of genres whose distinctions I have a hard time understanding. One of the main organizers is an English teacher, and he pulled in a lot of white faces, mixing in with the local b-boys and hipsters. One of the people he pulled in was an old friend I hadn't seen since last summer, a Chinese-American English teacher who is just about as nuts about cooking as I am.

While catching up with him and going over our current situations, it began to dawn on me just how rare the two of us are. Everything about English teaching jobs discourages people from striking out on their own, or carving out a niche in Japanese society. Housing is provided for or arranged by most schools, your job itself is a liminal space, the projection of Japanese dreams of "America". Inflated English teacher salaries heighten the unreality. Even socially it's easy to simply get caught up in the narrow network of teachers and foreigner friendly venues. People dissapear forever, back to their home country and their "real life", and Japan was a two year layover, a few photo albums to put on the shelf, a second gap year between graduation and a real career.

Although I crawled my way out of the claustrophobic English teaching circuit and out into lower paying, more personally satisfying work, there's nothing inherently wrong with that world, I've met many wonderful people through it. What I take issue with is the transient mentality it fosters; an extended vacation, a few years of sightseeing in your own neighborhood.

I am currently searching for apartments in my area, the second time I've been in Japan when I've had to go through this process. I would say that close to 80-85% of the landlords I talk to refuse a foreign tenant straight out because they have had a bad experience in the past. The sense of unreality, the lack of consequences leads people to kinds of behavior they wouldn't pull back home; from unproperly seperated trash and strings of noisy parties to unpaid bills and structural damage to the house, all sins are unreal, without consequences. This is Japan, and I'll be on the other side of the world in two months. One bad example is enough for most landlords, who simply don't want to put up with the hassle.

There has also been a rash of military personell and English teachers who routinely scam the trains, simply hopping the gates on the way in and the way out, the staff too busy or intimidated to do anything. If you were a five foot tall middle aged train conductor with a pension would you confront five linebacker built GI's for hopping the gates?

While these are all fairly petty, they add up to a pretty bad image for foreigners, even the clean cut English teacher types. I pretty much see immigration to Japan as a necessity, and myself at the forefront of a massive shift in Japanese society. Japan will never be my home, it is still a redshift away from the US; I have no desire to erase my Americanness. But it is no longer strange, and in many ways no longer foreign. All the pontification on Japanese uniqueness and being treated as an outsider are a mental denial of the inevitable, a multicultural Japan. What I realized last night when catching up with my friend was that whether you are here for two years or twenty, during that time you are not just in Japan, you are Japan.

...

Postscript:

There was an interesting editorial in Tokyo's free English weekly Metropolis a few weeks ago that takes such a radically different stance from my own but argues it so well that I can't get it out of my mind. Worth a look.

While catching up with him and going over our current situations, it began to dawn on me just how rare the two of us are. Everything about English teaching jobs discourages people from striking out on their own, or carving out a niche in Japanese society. Housing is provided for or arranged by most schools, your job itself is a liminal space, the projection of Japanese dreams of "America". Inflated English teacher salaries heighten the unreality. Even socially it's easy to simply get caught up in the narrow network of teachers and foreigner friendly venues. People dissapear forever, back to their home country and their "real life", and Japan was a two year layover, a few photo albums to put on the shelf, a second gap year between graduation and a real career.

Although I crawled my way out of the claustrophobic English teaching circuit and out into lower paying, more personally satisfying work, there's nothing inherently wrong with that world, I've met many wonderful people through it. What I take issue with is the transient mentality it fosters; an extended vacation, a few years of sightseeing in your own neighborhood.

I am currently searching for apartments in my area, the second time I've been in Japan when I've had to go through this process. I would say that close to 80-85% of the landlords I talk to refuse a foreign tenant straight out because they have had a bad experience in the past. The sense of unreality, the lack of consequences leads people to kinds of behavior they wouldn't pull back home; from unproperly seperated trash and strings of noisy parties to unpaid bills and structural damage to the house, all sins are unreal, without consequences. This is Japan, and I'll be on the other side of the world in two months. One bad example is enough for most landlords, who simply don't want to put up with the hassle.

There has also been a rash of military personell and English teachers who routinely scam the trains, simply hopping the gates on the way in and the way out, the staff too busy or intimidated to do anything. If you were a five foot tall middle aged train conductor with a pension would you confront five linebacker built GI's for hopping the gates?

While these are all fairly petty, they add up to a pretty bad image for foreigners, even the clean cut English teacher types. I pretty much see immigration to Japan as a necessity, and myself at the forefront of a massive shift in Japanese society. Japan will never be my home, it is still a redshift away from the US; I have no desire to erase my Americanness. But it is no longer strange, and in many ways no longer foreign. All the pontification on Japanese uniqueness and being treated as an outsider are a mental denial of the inevitable, a multicultural Japan. What I realized last night when catching up with my friend was that whether you are here for two years or twenty, during that time you are not just in Japan, you are Japan.

...

Postscript:

There was an interesting editorial in Tokyo's free English weekly Metropolis a few weeks ago that takes such a radically different stance from my own but argues it so well that I can't get it out of my mind. Worth a look.

Wednesday, February 02, 2005

smarmy

There was some psychology experiment I read about last year where some researchers tested people's stress levels when shown pictures of George W., Clinton, Rush Limbaugh and other polarizing political figures. Not surprisingly, the subjects political affiliations determined whether they would get pissed off by just looking at a picture of George W. for a few seconds. I know that I certainly derive a pervserse satisfaction from looking at Bush pictures and feeling the rise in my gut that just reviles the guy. Putting his policies aside, I dislike the way he does the things, the smirk he wears, the childish little outbursts during the debates. ("Hey, my job is really hard. I go over all the data. That's a tough job.") Clinton and Reagan may have gutted US labor, waged a few wars here and there and mushroomed the US prisons to o.7% of the population, but I could at least sit down and have a beer and a civil discussion with those guys. I think I would have a hard time not just yelling and spitting like a feral cat if you put me near W.

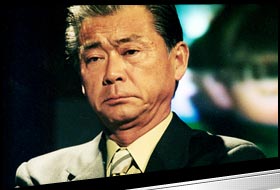

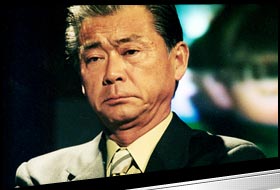

One of the pluses about being an ex-pat in Japan is you can just bliss out, let the cultural and language gap insulate you from many of the domestic problems here, and envision Japan to be as perfect or as imperfect as you want, going only on the trickle of information available in English and your daily experiences. While Japanese government remains a mystery to me, I've been learning a lot of cultural icons lately, and was surprised to find one I react to almost as strongly as Bush. Foreigners in Japan, here is the face of the enemy:

This smarmy face first drifted into my consciousness when I happened to stumble upon the Japanese version of "Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?" on TV (they give away a million yen, not quite as exciting as a million dollars), and wondered who that greasy host was. He just seemed to be another face in the sea of Japanese tarento, "talent", the ranks of the professionally famous who litter Japanese talk shows, and don't have do anything else than be famous to get on.

Soon that face was popping up everywhere in my life, like when I was browsing beers, and came upon this horriying little gremlin from Ginga Kogen, normally an excellent Nagano brewery:

This is Oyasumi biru, "Goodnight Beer", an unsettling little nightcap for the hard working Japanese man over 40. Seeing the guys face rankled me something fierce; I mean, have you ever seen a smile so disingenuous?

In anycase, my suspicions were correct. This man is Mino Monta, beloved spokesperson of Japan's graying generation, the postwar economic warriors who look out at the country they built with horror and revulsion. Over the New Years break I was eating one dinner in front of the TV, and stumbled upon a show hosted by Mino Monta that "exposed" the way South East Asian prostitutes were destroying Japanese downtowns. These poor women, often brought to Japan under false promises of entertainment work and frequently kept in abusive situations by yakuza employers, were vilified as "corrupting foreigners" who are destroying Japan's peace and innocence. Mino Monta took a kind of lurid morally superior satisfaction in condemning the whorehouses that lined main streets frequented by commuting school children. There was absolutely no mention made of the fact that all the employers and customers who actually created the situation are Japanese. Apparently this show is on every week, it's only theme the way foreigners are degrading Japanese society.

The other night I spotted another Mino Monta hosted show during dinner, and my lurid curiosity got the better of me. The title alone got me pissed off: Yo no naka de, kore wa yurusenai!, loosely translated, "This is Absolutely Unforgiveable!" Mino Monta and a carefully selected panel of older or conservatively young tarento talked about how Japan's youth are going to the pits. Their roaming reporter did man on the street interviews with older people, with his killer lead off question: "What pisses you off about young people today?" I found the reporter's aggressive tactics more unforgiveable than anything they exposed. At one point the guy bursts in, uninvited, to a booth in an internet cafe in Akihabara, where young computer geeks, paying by the hour, are typing away feverishly. One of them, showing remarkable restraint and tact, answered the questions that came at a furious pace. "How long have you been in here?" "Five hours... instant messaging online." "What, you don't like to talk to people!? Hey you [gesturing at a guy in the corner who is ignoring the camera and continues typing], what you don't like talking?" "Well, for some people it's easier to express themselves online, it's not as much pressure..." "How many friends do you have?", and so on and so on.

They also featured a "representative" panel of young people, ganguro kids and fashion victims, who only spoke in an impenetrable slang, which Mino Monta and the panel proceeded to attack straight out: "Why don't you talk normally! I can't understand what you're saying!" While most of them just stared back, jaws slack, one young man responded: "That's kind of the point." I know where he's coming from.

rrrrrrrrrrrrrr, I just hate this guy.

One of the pluses about being an ex-pat in Japan is you can just bliss out, let the cultural and language gap insulate you from many of the domestic problems here, and envision Japan to be as perfect or as imperfect as you want, going only on the trickle of information available in English and your daily experiences. While Japanese government remains a mystery to me, I've been learning a lot of cultural icons lately, and was surprised to find one I react to almost as strongly as Bush. Foreigners in Japan, here is the face of the enemy:

This smarmy face first drifted into my consciousness when I happened to stumble upon the Japanese version of "Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?" on TV (they give away a million yen, not quite as exciting as a million dollars), and wondered who that greasy host was. He just seemed to be another face in the sea of Japanese tarento, "talent", the ranks of the professionally famous who litter Japanese talk shows, and don't have do anything else than be famous to get on.

Soon that face was popping up everywhere in my life, like when I was browsing beers, and came upon this horriying little gremlin from Ginga Kogen, normally an excellent Nagano brewery:

This is Oyasumi biru, "Goodnight Beer", an unsettling little nightcap for the hard working Japanese man over 40. Seeing the guys face rankled me something fierce; I mean, have you ever seen a smile so disingenuous?

In anycase, my suspicions were correct. This man is Mino Monta, beloved spokesperson of Japan's graying generation, the postwar economic warriors who look out at the country they built with horror and revulsion. Over the New Years break I was eating one dinner in front of the TV, and stumbled upon a show hosted by Mino Monta that "exposed" the way South East Asian prostitutes were destroying Japanese downtowns. These poor women, often brought to Japan under false promises of entertainment work and frequently kept in abusive situations by yakuza employers, were vilified as "corrupting foreigners" who are destroying Japan's peace and innocence. Mino Monta took a kind of lurid morally superior satisfaction in condemning the whorehouses that lined main streets frequented by commuting school children. There was absolutely no mention made of the fact that all the employers and customers who actually created the situation are Japanese. Apparently this show is on every week, it's only theme the way foreigners are degrading Japanese society.

The other night I spotted another Mino Monta hosted show during dinner, and my lurid curiosity got the better of me. The title alone got me pissed off: Yo no naka de, kore wa yurusenai!, loosely translated, "This is Absolutely Unforgiveable!" Mino Monta and a carefully selected panel of older or conservatively young tarento talked about how Japan's youth are going to the pits. Their roaming reporter did man on the street interviews with older people, with his killer lead off question: "What pisses you off about young people today?" I found the reporter's aggressive tactics more unforgiveable than anything they exposed. At one point the guy bursts in, uninvited, to a booth in an internet cafe in Akihabara, where young computer geeks, paying by the hour, are typing away feverishly. One of them, showing remarkable restraint and tact, answered the questions that came at a furious pace. "How long have you been in here?" "Five hours... instant messaging online." "What, you don't like to talk to people!? Hey you [gesturing at a guy in the corner who is ignoring the camera and continues typing], what you don't like talking?" "Well, for some people it's easier to express themselves online, it's not as much pressure..." "How many friends do you have?", and so on and so on.

They also featured a "representative" panel of young people, ganguro kids and fashion victims, who only spoke in an impenetrable slang, which Mino Monta and the panel proceeded to attack straight out: "Why don't you talk normally! I can't understand what you're saying!" While most of them just stared back, jaws slack, one young man responded: "That's kind of the point." I know where he's coming from.

rrrrrrrrrrrrrr, I just hate this guy.

Monday, January 31, 2005

the other side of the pond

There is an advertisement that has been frequenting Tokyo trains recently. Despite its muted tones and simple layout it popped out at me amid all the ads for fashion magazines, cram schools, beer and laxatives. It is a photograph of a New York art studio, fashionable but not unrealistic, with two young women, a Caucasian and an Asian, working intensely on some pottery. They're both wearing no nonsense loose clothing, no trace of feminine appeal or obsequious fashionability about it. Although I can't be 100% sure, the photograph stands out from all the other hyper-real images in Tokyo advertising of air brushed and CG'd models hawking canned soup and skin products in that it seems to be a real situation, no touching up or even dramatic framing or angles. Overlaying the photo is the text, "I discovered the real me in New York City"; the internship linkup agency's contact info runs along the bottom edge.

Interestingly enough, there is an article and a photo essay in today's New York Times about the recent wave of young issei, first generation Japanese immigrants who flock to New York City as a place where they can freely pursue careers in the arts and find a better sense of themselves. The article is very well done, but didn't address one issue that I'm sure a lot of the issei are worried about: visas. I have met a string of young Japanese who have lived abroad for a significant period of time, but what with the US cracking down on foreign visas (particularly student visas), many of them were cut short and came back to a Japan they could barely relate to.

I used to work with one young Japanese chef who had gone to culinary school in Manhattan, had worked and interned at some of the best French and fusion restaurants in NYC, and was just getting settled in when her visa extension was denied and she flew back to Japan, her culinary credentials worth very little. Loyalty and seniority counts for a lot in Japan, and while moving around within the restaurant world and stacking up a list of internships is fairly common in the US, in Japan it's morecommon to get the Yoda treatment: intense and extensive training in a single kitchen. I met a young guy about my age the other night who works in a small kaiseki restaurant, Japan's haute cuisine. He has been working in the same three person kitchen for six years, and he told me that "I'm only just beginning to understand proper kaiseki."

Anyway, you could tell the girl was pure New York at one glance; she came to her interview on one of those mountain bikes you only see in the city, headphones snaking out from a pocket in her windbreaker, sporty sunglasses and her knife set tucked into a bike messenger bag. She didn't gel well with Japan at all; too gregarious, opinionated, and tough. One of the excellent details the NY Times article picks up on is how the Japanese femininity that squeezes voices higher loosens up in New York, with expat women speaking in deeper and more natural voices. There are a thousand little social cues like this that bind Japanese girls, from the prevalence of high heels and short skirts to a personality that avoids asserting itself too strongly. My friend was lucky enough to work for an American owned restaurant, but even then she was socially stranded, her quirks and aggressive personality just bowling over Japanese coworkers. She lasted a few months, but she's currently back in New York at a small fusion place in SoHo, working in three month visitor visa chunks, flying back to Japan every ninety days for a renewal.

Interestingly enough, there is an article and a photo essay in today's New York Times about the recent wave of young issei, first generation Japanese immigrants who flock to New York City as a place where they can freely pursue careers in the arts and find a better sense of themselves. The article is very well done, but didn't address one issue that I'm sure a lot of the issei are worried about: visas. I have met a string of young Japanese who have lived abroad for a significant period of time, but what with the US cracking down on foreign visas (particularly student visas), many of them were cut short and came back to a Japan they could barely relate to.

I used to work with one young Japanese chef who had gone to culinary school in Manhattan, had worked and interned at some of the best French and fusion restaurants in NYC, and was just getting settled in when her visa extension was denied and she flew back to Japan, her culinary credentials worth very little. Loyalty and seniority counts for a lot in Japan, and while moving around within the restaurant world and stacking up a list of internships is fairly common in the US, in Japan it's morecommon to get the Yoda treatment: intense and extensive training in a single kitchen. I met a young guy about my age the other night who works in a small kaiseki restaurant, Japan's haute cuisine. He has been working in the same three person kitchen for six years, and he told me that "I'm only just beginning to understand proper kaiseki."

Anyway, you could tell the girl was pure New York at one glance; she came to her interview on one of those mountain bikes you only see in the city, headphones snaking out from a pocket in her windbreaker, sporty sunglasses and her knife set tucked into a bike messenger bag. She didn't gel well with Japan at all; too gregarious, opinionated, and tough. One of the excellent details the NY Times article picks up on is how the Japanese femininity that squeezes voices higher loosens up in New York, with expat women speaking in deeper and more natural voices. There are a thousand little social cues like this that bind Japanese girls, from the prevalence of high heels and short skirts to a personality that avoids asserting itself too strongly. My friend was lucky enough to work for an American owned restaurant, but even then she was socially stranded, her quirks and aggressive personality just bowling over Japanese coworkers. She lasted a few months, but she's currently back in New York at a small fusion place in SoHo, working in three month visitor visa chunks, flying back to Japan every ninety days for a renewal.

Friday, January 28, 2005

nowhere, japan

Up til now I've basically relied on the loose metaphor that Saitama is Tokyo's New Jersey, and have said a few things about how it's very anonymity and lack of local distinguishing color makes it feel like one of the most thoroughly Japanese of all places I've been to.

Obviously every place in Japan is Japanese by definition, but it's a loose thing, this Japaneseness, more of a modern invention of mass communication than anything else. Just a hundred years ago the country was awash in impenetrable local dialects and regional customs. One of the classic examples is natto, fermented soybeans coated in this sticky goo, mixed with some sauce and mustard, usually eaten over rice. It also stinks to high heaven, like the smelliest cheese you could never actually bear to bring to your mouth. While people in Eastern Japan (including Tokyo) eat this stuff for breakfast, it's only just barely starting to be sold in the Kansai area (Kyoto, Osaka, Kobe).

In anycase, Saitama seemed distinct by its very lack of character. It is a prefecture of people who came from somewhere else, from cold little hamlets and one horse towns, coming to the big city, ending up in Saitama where the rents are lower and the groceries cheaper. In my two years here almost comes from some little town I've never heard of, or they have grandparents whose speech they can't understand. Uprooted from their hometowns and transplanted to the rough Kanto soil makes for a lot of lost souls. It's a pet theory of mine that the idea of a national Japanese identity only came into being with the massive move to the cities, and the advent of television.

At any rate, Saitama is concurrent in many people's minds to Japan at it's most bland and characterless. Saitama's nickname is "Dasaitama". Dasai is an adjective reserved for the likes of mullets, Pauly Shore movies and New Jersey. But with a prefectural population topping seven million, that is a lot of people to be calling lame, and something resembling local pride is starting to crop up.

It's remarkable how America exports both the image of "normal" modern life and the modern images of rebellion to other countries. Following this odd phenomenon, hip-hop is absolutely huge in urban Saitama. Although the bulk of hip-hop in Japan, like in the US is about cool cars, cool clothes and booty dancing honeys, the strain of hip-hop that pumps local pride and the empowerment from local hip-hop scenes has survived the trans-Pacific journey. It seems to cling fastest to those places blighted worst by urban development, the liminal gray zones of apartment blocks and corner factories. In my old neighborhood in Western Saitama the quiet train station was often overtaken by scores of hip-hop kids who brought in boom boxes and practiced breakdancing moves with their friends. They would use the broad windows as mirrors to check their moves. I never saw anything resembling a 40, and you better believe most of these kids had never even smelled a blunt.

Across the border in Tokyo prefecture (the distinction is pretty meaningless, the urban sprawl being pretty constant the whole way), hip-hop also thrives in the suburbs. Last year there was a major hit from a group called the Ota Crew, whose name is a pun on their hometown, Ota-ku, the largest ward in Tokyo. In my loose translation, the chorus of their hit went something like"In the alphabet it's O-T-A!/Biggest of the 23 wards in Tokyo ze!/In the alphabet it's O-T-A!/Feeling a'ight in the Keihin area today!"

But back to Saitama. The other night a local English teacher showed me his local watering hole, Riki. (Google translation software!) I'd walked by it a few times before, this rowdy Japanese style bar smack in the center of downtown Urawa, on a central corner in the middle of the pedestrian shopping area, with tables that spill out into the street even in January. There's a counter right on the corner with several baskets of yakitoris skewers, steaming in the January air, bought by hungry commuters grabbing a take-away snack for the walk home. It is emblazoned with posters that scream "We Are Reds!" in English, which I thought was pretty awesome, until I realized The Reds are the local soccer team. While the season is over now, this place is ground zero for fans who can't make it into the stadium during games. The Reds are the longest running soccer team in Japan, and for a long time they were the only major sports team in Saitama, lacking even a baseball team. As such they inspire fanatic loyalty in their fans, and my friend told me this place gets insane during games. The street will be jammed in every direction and they'll still be serving everyone, waitresses lugging pitchers of beer and ticking off orders on the little clipboard slips they leave with every customer.

The Reds took the championship this year, and while my memory of the story is fogged by all the beer on my brain when I heard it, Riki's was apparently the epicenter of the riot-party that followed. Urawa's downtown was brimming with whooping elated fans awash in alcohol and maniacal good spirits. Funny, but the only other time I've seen that type of thing here are at the local festivals, in the hometowns Saitama folk left behind.

Obviously every place in Japan is Japanese by definition, but it's a loose thing, this Japaneseness, more of a modern invention of mass communication than anything else. Just a hundred years ago the country was awash in impenetrable local dialects and regional customs. One of the classic examples is natto, fermented soybeans coated in this sticky goo, mixed with some sauce and mustard, usually eaten over rice. It also stinks to high heaven, like the smelliest cheese you could never actually bear to bring to your mouth. While people in Eastern Japan (including Tokyo) eat this stuff for breakfast, it's only just barely starting to be sold in the Kansai area (Kyoto, Osaka, Kobe).

In anycase, Saitama seemed distinct by its very lack of character. It is a prefecture of people who came from somewhere else, from cold little hamlets and one horse towns, coming to the big city, ending up in Saitama where the rents are lower and the groceries cheaper. In my two years here almost comes from some little town I've never heard of, or they have grandparents whose speech they can't understand. Uprooted from their hometowns and transplanted to the rough Kanto soil makes for a lot of lost souls. It's a pet theory of mine that the idea of a national Japanese identity only came into being with the massive move to the cities, and the advent of television.

At any rate, Saitama is concurrent in many people's minds to Japan at it's most bland and characterless. Saitama's nickname is "Dasaitama". Dasai is an adjective reserved for the likes of mullets, Pauly Shore movies and New Jersey. But with a prefectural population topping seven million, that is a lot of people to be calling lame, and something resembling local pride is starting to crop up.

It's remarkable how America exports both the image of "normal" modern life and the modern images of rebellion to other countries. Following this odd phenomenon, hip-hop is absolutely huge in urban Saitama. Although the bulk of hip-hop in Japan, like in the US is about cool cars, cool clothes and booty dancing honeys, the strain of hip-hop that pumps local pride and the empowerment from local hip-hop scenes has survived the trans-Pacific journey. It seems to cling fastest to those places blighted worst by urban development, the liminal gray zones of apartment blocks and corner factories. In my old neighborhood in Western Saitama the quiet train station was often overtaken by scores of hip-hop kids who brought in boom boxes and practiced breakdancing moves with their friends. They would use the broad windows as mirrors to check their moves. I never saw anything resembling a 40, and you better believe most of these kids had never even smelled a blunt.

Across the border in Tokyo prefecture (the distinction is pretty meaningless, the urban sprawl being pretty constant the whole way), hip-hop also thrives in the suburbs. Last year there was a major hit from a group called the Ota Crew, whose name is a pun on their hometown, Ota-ku, the largest ward in Tokyo. In my loose translation, the chorus of their hit went something like"In the alphabet it's O-T-A!/Biggest of the 23 wards in Tokyo ze!/In the alphabet it's O-T-A!/Feeling a'ight in the Keihin area today!"

But back to Saitama. The other night a local English teacher showed me his local watering hole, Riki. (Google translation software!) I'd walked by it a few times before, this rowdy Japanese style bar smack in the center of downtown Urawa, on a central corner in the middle of the pedestrian shopping area, with tables that spill out into the street even in January. There's a counter right on the corner with several baskets of yakitoris skewers, steaming in the January air, bought by hungry commuters grabbing a take-away snack for the walk home. It is emblazoned with posters that scream "We Are Reds!" in English, which I thought was pretty awesome, until I realized The Reds are the local soccer team. While the season is over now, this place is ground zero for fans who can't make it into the stadium during games. The Reds are the longest running soccer team in Japan, and for a long time they were the only major sports team in Saitama, lacking even a baseball team. As such they inspire fanatic loyalty in their fans, and my friend told me this place gets insane during games. The street will be jammed in every direction and they'll still be serving everyone, waitresses lugging pitchers of beer and ticking off orders on the little clipboard slips they leave with every customer.

The Reds took the championship this year, and while my memory of the story is fogged by all the beer on my brain when I heard it, Riki's was apparently the epicenter of the riot-party that followed. Urawa's downtown was brimming with whooping elated fans awash in alcohol and maniacal good spirits. Funny, but the only other time I've seen that type of thing here are at the local festivals, in the hometowns Saitama folk left behind.

Wednesday, January 26, 2005

keigo

Japanese is a notoriously difficult language.

Everyone says so.

If I had a nickel for every time someone here told me that "Japanese is difficult even for us Japanese", I would have a lot of nickels. Unfortunately my corner grocery doesn't take nickels.

Although Japanese is an orphan on the linguistic tree, huddled along with Korean as a grammatical anomaly, this is not what people mean when they say Japanese is difficult. One of the many complaints lodged at today's Japanese youth is that they can't speak proper keigo, the high wire act of formal speaking that gilds everyday spoken Japanese with a glut of formal terms. In it's roughest and most simple form, "What will you eat?" can be grunted out as "Nani ku?" but in keigo it could come out as "Go-shokuji wa nani o meshiagaru desho ka?" Keigo is not something spoken naturally, but requires study and effort. It's not an uncommon sight to see people studying books like "How to Use Business Keigo" on the train. Lacarated keigo is a television staple, with whole shows based around famous comedians put in delicate situations, forced to use proper language and failing miserably.

No matter how far along I progress in my own Japanese study, proper keigo remains a mystery, the very peak of Japanese study. Conversational Japanese is clipped and quick, whole sentences sometimes pared down to a single key word understood by context, but keigo gilds those phrases with loads of florid embellishments. This in and of it itself is not impossible, but most difficult for non-native Japanese speakers is not just learning formal language but using it appropriately. I was once out drinking with a friend who had studied quite a bit of Japanese in the States and could speak fairly well, but had only been in Japan for a few weeks. When we started talking to the group next to us, he completely broke the tone by standing up, bowing, and reciting verbatim the standard formal greeting that everyone learns on the first day of Japanese class. That's great when new business partners and textbook mainstays Tanaka-san and Smith-san meet for the first time, but not so applicable in a rowdy Japanese bar.

The danger for most of us who have been here too long is speaking too informally. As a token white guy you tend to get introduced to a lot of important people in rural areas; I've let some pretty rough sentences slip while making small talk with the local mayor, who, politician that he is, registers a mild shock, then proceeds to hug the foreigners and kiss the babies.

Keigo may just sound like a useless formality, but on another level it reflects a universal psychological reality. Although it's not laid out formally we have a host of these in English. My favorite is calling a company and starting off with "I was just wondering if..." Really? You were just sitting around idly wondering if there were any brake pads in stock, and once you find out, your curiosity can be put to rest? Japanese keigo is infamous for this kind of indirect language, but the only real distinction between it and formal English is that in Japanese they are laid out in neat little tables.

Everyone says so.

If I had a nickel for every time someone here told me that "Japanese is difficult even for us Japanese", I would have a lot of nickels. Unfortunately my corner grocery doesn't take nickels.

Although Japanese is an orphan on the linguistic tree, huddled along with Korean as a grammatical anomaly, this is not what people mean when they say Japanese is difficult. One of the many complaints lodged at today's Japanese youth is that they can't speak proper keigo, the high wire act of formal speaking that gilds everyday spoken Japanese with a glut of formal terms. In it's roughest and most simple form, "What will you eat?" can be grunted out as "Nani ku?" but in keigo it could come out as "Go-shokuji wa nani o meshiagaru desho ka?" Keigo is not something spoken naturally, but requires study and effort. It's not an uncommon sight to see people studying books like "How to Use Business Keigo" on the train. Lacarated keigo is a television staple, with whole shows based around famous comedians put in delicate situations, forced to use proper language and failing miserably.

No matter how far along I progress in my own Japanese study, proper keigo remains a mystery, the very peak of Japanese study. Conversational Japanese is clipped and quick, whole sentences sometimes pared down to a single key word understood by context, but keigo gilds those phrases with loads of florid embellishments. This in and of it itself is not impossible, but most difficult for non-native Japanese speakers is not just learning formal language but using it appropriately. I was once out drinking with a friend who had studied quite a bit of Japanese in the States and could speak fairly well, but had only been in Japan for a few weeks. When we started talking to the group next to us, he completely broke the tone by standing up, bowing, and reciting verbatim the standard formal greeting that everyone learns on the first day of Japanese class. That's great when new business partners and textbook mainstays Tanaka-san and Smith-san meet for the first time, but not so applicable in a rowdy Japanese bar.

The danger for most of us who have been here too long is speaking too informally. As a token white guy you tend to get introduced to a lot of important people in rural areas; I've let some pretty rough sentences slip while making small talk with the local mayor, who, politician that he is, registers a mild shock, then proceeds to hug the foreigners and kiss the babies.

Keigo may just sound like a useless formality, but on another level it reflects a universal psychological reality. Although it's not laid out formally we have a host of these in English. My favorite is calling a company and starting off with "I was just wondering if..." Really? You were just sitting around idly wondering if there were any brake pads in stock, and once you find out, your curiosity can be put to rest? Japanese keigo is infamous for this kind of indirect language, but the only real distinction between it and formal English is that in Japanese they are laid out in neat little tables.

Monday, January 24, 2005

and now for something completely different..

Just found an excellent blog written in English by a young Iraqi woman, Baghdad Burning.

Sunday, January 23, 2005

seafood

It's time to come clean. I mean, it's been years since I engaged in anything like that. Hell, I washed myself clean with years of hardcore punk shows in Cleveland and avant-garde performances in Manhattan. I haven't smoked pot in... well, can't remember the last time. Anyway, I can now confidently admit that my name is Jamie, and I am a former Phish-head.

As a middle school student who couldn't dribble a basketball for his life, came close to tears when being hit in dodgeball and who liked music but found the choir geeks just too... creepy, finding the local jam band scene was a sign from heaven that there was more to life than cafeteria seating politics.

After going through a few years of drugs, rock and roll and absolutely no sex, I discovered jazz and exchanged dope and Phish for coffee and chord substitutions. Jam Band music just seems kind of emotionally facile to me, hard to listen to music that is so comfortably happy in a world that is so resolutely not. I finished out high school clean as a whistle and with a new vocabulary that included words like "cat", "four-to-the-floor", "II-V-I's", "C blues" and "dig." Ergo: "That Jim Hall is one serious cat, he was ripping through this four-to-the-floor C blues just dripping with II-V-I subsitutions. Dig?"